Beyond the standard inclusion of images in many web sites, I have not seen many web-sites where the illustration or photography itself drives the design. Those of you that are illustrators and photographers might want to consider such an ideal, using your ability to illustrate and take pictures to design the whole user experience. Incorporation the images into the design will develop a signature look that can be used to sell a product, which by its very nature will stand out from similar in the design itself increases its attractiveness for commercial use.

The most common approach is to place one large illustration on a page with a few links. While this is the most expedient way to use one’s illustration, it does not make for good web design.

Good web design has to be much more flexible than one large image, and that flexibility is gained by breaking the illustration up into many modular parts. The strategy is to take these parts and use them in the background of the elements that make up the design.

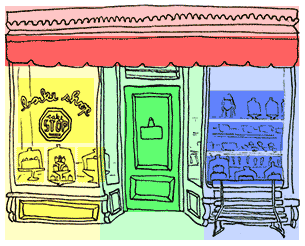

Take a front end store design. This is an illustration that can easily be divided up into a classic three column layout with a header.

Great! Then all you have to do is create areas in each column where there is content. The menu could go into the header and the two windows and the door could contain all kinds of products.

Or is it that great? What happens if there’s more text than can easily fit into the required space? Is the design flexible enough to adapt to the additional content?

What happens to the design if it is seen on an iPhone or a 30inch monitor?

It quickly feels like it’s not flexible, and that is missing the point of designing for the web. Being flexible is a key component of web design. You have to design with this flexible nature in mind, using your illustrations or photographs in a more modular fashion.

Attaching the art to the background

The first step is to place your image in the background. That’s simple enough! Use the background property and specify the url() as in the h2 above that’s targeted by this demonstration. It uses the illustration at the top of the page. Change the padding on the top and bottom to show more of the image. Move the image around by changing the x and y positions or use left, center, right, top, center and bottom keywords. Ad in the same image more than one. The second image is positioned so the bottom of the illustration shows up on top of the header.

CSS Code View

Be careful with how you write the css, because it’s not tolerant of mistakes. If it turns out that you are not able to see your image, simplify the code till you see it working, and then add in the x and y positioning properties. One misplaced character and the background disappears.

Sprites

Once you become familiar with placing background images, it’s easy to imagine that you’ll do it often.

It turns out that the penalty for initiating the connection that retrieves each image from the server is greater than the penalty it takes to actually retrieve the image. So if you have a lot of images, it’s recommended to turn each of your images into a sprite. This means to combine them into one file, with a lot of empty space around each picture, and to call them up by using the x and y coordinates.

This would be a cumbersome if it were not for Sprite Cow (and similar web applications). We used it earlier in the article on Styling the Navigation. It provide you with the coordinates and the size for each picture within the page of pictures, and this is then called a sprite.

If your images are small, you can use the 24bit png format, which includes a nice alpha channel that allows you to layer background images on top of one another. The size of the image grows pretty quickly, however, and if you are not going to layer the images, use jpeg compression. The “Pick Background” button in Sprite Cow will isolate the background. Note that compression quality under 60% will add noise to the edges of your sprite, which has to be adjusted for when you use it.

After placing all of your images in photoshop in separate layers, moving them to individual locations and saving the file for the web, you load it into Sprite Cow. Click on each image. If several images belong to one sprite, drag the pointer over them to select them all.

The code for the sprite appears at the bottom left hand side. Copy this code and paste it into your stylesheet, update the location of the image, and you have a background sprite ready to use in the layout. Do this for each sprite, and that’s how to gang up lots of pictures into one image, greatly saving on the time it would take to load all of the pictures individually.

Using Background Images

A layout can be thought of as boxes stacked one below the other, and then however many to the right of one another. This down and across movement is how to build out the layout of the web page in the word processor like environment of the default document flow.

Chances are the layout is developed in Photoshop or Illustrator, where it’s easy enough to figure out where the boxes should be to hold the graphics, text and other design elements. Develop those boxes first, and that becomes your wireframe. Plugging in your picture, or multiple pictures is then as easy as assigning the code produced by Sprite Cow to any box.

Adapting Background Images for Responsive Layouts

Working with sprites is all great when working on a single layout, but what about responsive layouts? This can be a little more complicated. Responsive design means that you have to develop several photoshop comps to represent what the web page will look like on the iPhone or Android and tablet, where it can appear either horizontally or vertically, or a small to large computer monitors, which tend to stay horizontal.

All of this means that the website has to be scaled from the 320 pixel standard of the original iPhone to windows in excess of 1920 pixels wide, usually in a number of increments, typically including 480, 600, 768, 992 and 1382 pixels. The design stage in Photoshop makes it clear that the 320 pixel version will need to condense and collapse a lot of the information. Chances are that the background images will likely appear smaller, or be eliminated all together from the iPhone layout.

Some of this can be handled by creating several sets of images, depending on the device. That way the iPhone does not attempt to download images the the iPhone layout might not even use. But even if we were to duplicate the images into three sizes, it still might be desirable to shrink images between the 320 pixel vertical layout and the 480 pixel horizontal layout. That’s a 1.5 difference in size when you turn the phone’s orientation.

Changing the background image is easy enough, using the CSS property background-size: 66%; for the vertical and background-size: 100%; for the horizontal layout. But this means that the entire sprite is sized, and the original coordinates need to be multiplied by 1.5 to locate the image on the sprite.

One way to make this easier is to place the images on a grid of even intervals so the coordinates can be easily multiplied. If each image is on a grid of 300 pixels, its easier to calculate this difference. But know that it is a very inflexible way to approach the problem, and its probably better to ignore making sprites till the very end of the process if you plan on changing the sizes of the background images.

I hope to have an example up so you can see this process for yourself. but know that this entire responsive layout business is too new to have best practices associated with it.